Más despacio, por favor

Slow down, you learn too fast

When my children were in the 7th grade in a San Francisco public school, parents and teachers had to make an important decision for the year ahead. Should students take algebra or 8th grade math?

This was not a random question. Low math achievement was driving a major rethink of how to teach math. Civil rights advocates started to call algebra the “new civil right” to address low success rates of students of color. Others compared US math achievement to higher-performing countries in Asia and advocated that the United States copy those strategies: Move algebra to the 8th grade.

Yet, when I met with my son’s math teacher — who had taught math for decades — her answer was unequivocal: Don't rush. Take 8th grade math. Develop a thorough understanding of math concepts. This is not a race to see who can take the most math courses.

Proposal to change California Math Frameworks

Parents and students today are confronting the same issue that my son faced in the '90s. California is in the midst of updating its mathematics frameworks, which provide guidance to educators, parents, and publishers about how to implement California content standards. The updated frameworks are scheduled to go before the State Board of Education in November, 2021. Debates over de-tracking classes and what students should learn and when they should learn it aren't just a California issue. States all over the country are grappling with this.

Here’s the background

Before the 1990s, access to algebra in the 8th grade was extremely limited and many students of color were left out of higher levels of math.

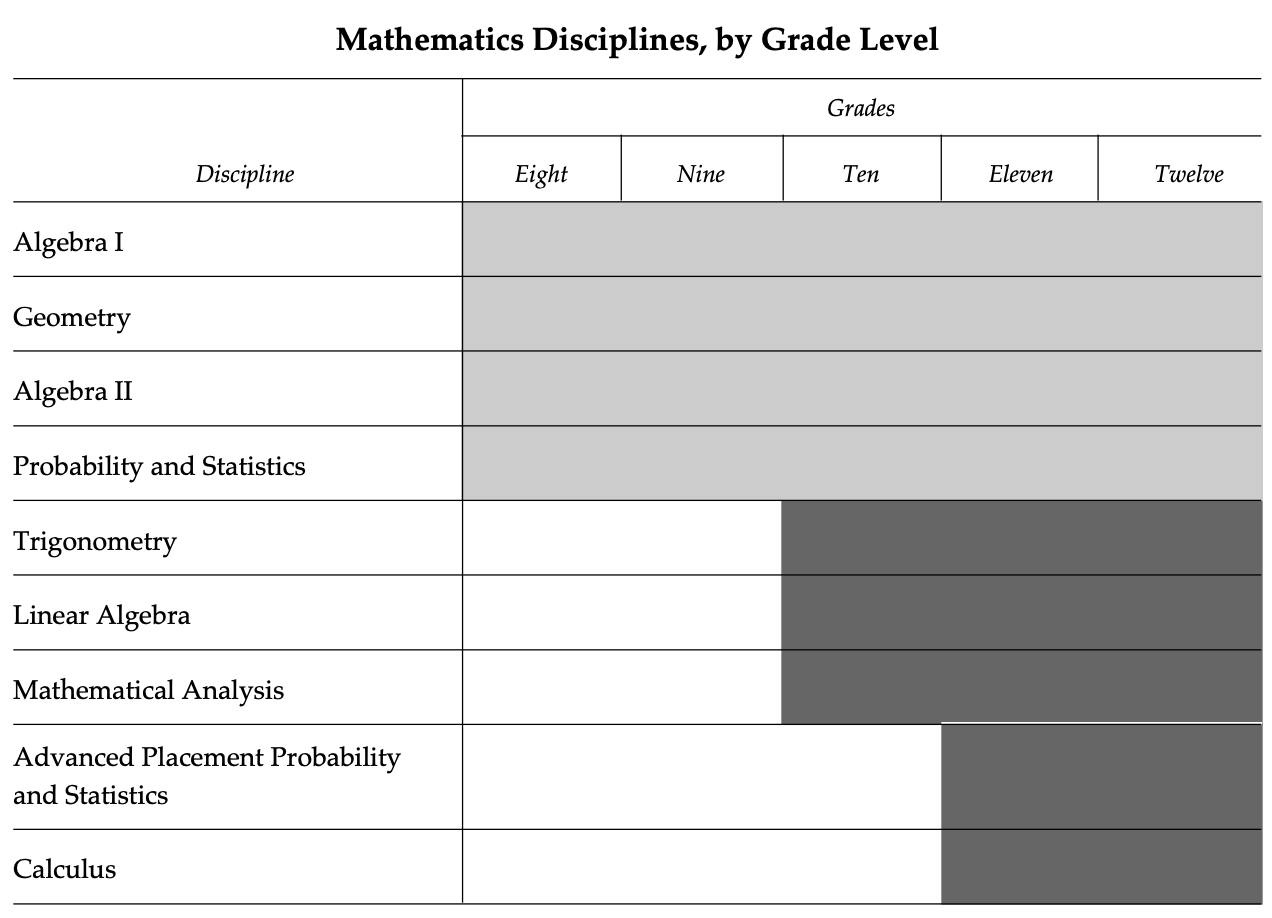

In 1997, California responded to this problem by changing its statewide math content standards, driving a faster pace for math learning. Algebra 1 was added to the 8th grade curriculum.

This change at the top of grade-level math expectations drove a dramatic increase in enrollment in 8th grade algebra. From 1999 through the peak in about 2014, a large number of schools added algebra to their math offerings in the 8th grade. Thousands of middle school students began taking algebra in middle school, including unprecedented numbers of students from areas of high poverty. The subsequent decline in algebra enrollment in the chart below mirrors the dates for California's adoption of Common Core math standards, which changed the standard course sequence and moved algebra to the 9th grade.

In addition to the mismatch with the Common Core sequence, some researchers have questioned the premise. Does pushing students to enroll in algebra in 8th grade actually result in more widespread mathematical understanding? Do more students take higher level math — and when they do, do they succeed?

“Although policymakers have intended algebra for all to democratize access to college and learning success (Moses, 1995), Loveless (2008) viewed this mantra as a false democratization. He concluded, “No social benefit is produced by placing students in classes for which they are unprepared. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine any educational benefit accruing to these students”.

A review of the research by the Brookings Institute underscored the complexity of interpreting data about this large experiment in course sequencing. While “many students benefit from the extra challenge, the downside is that the number of students failing algebra goes up as well; and the failing students... are disproportionately poor and students of color."

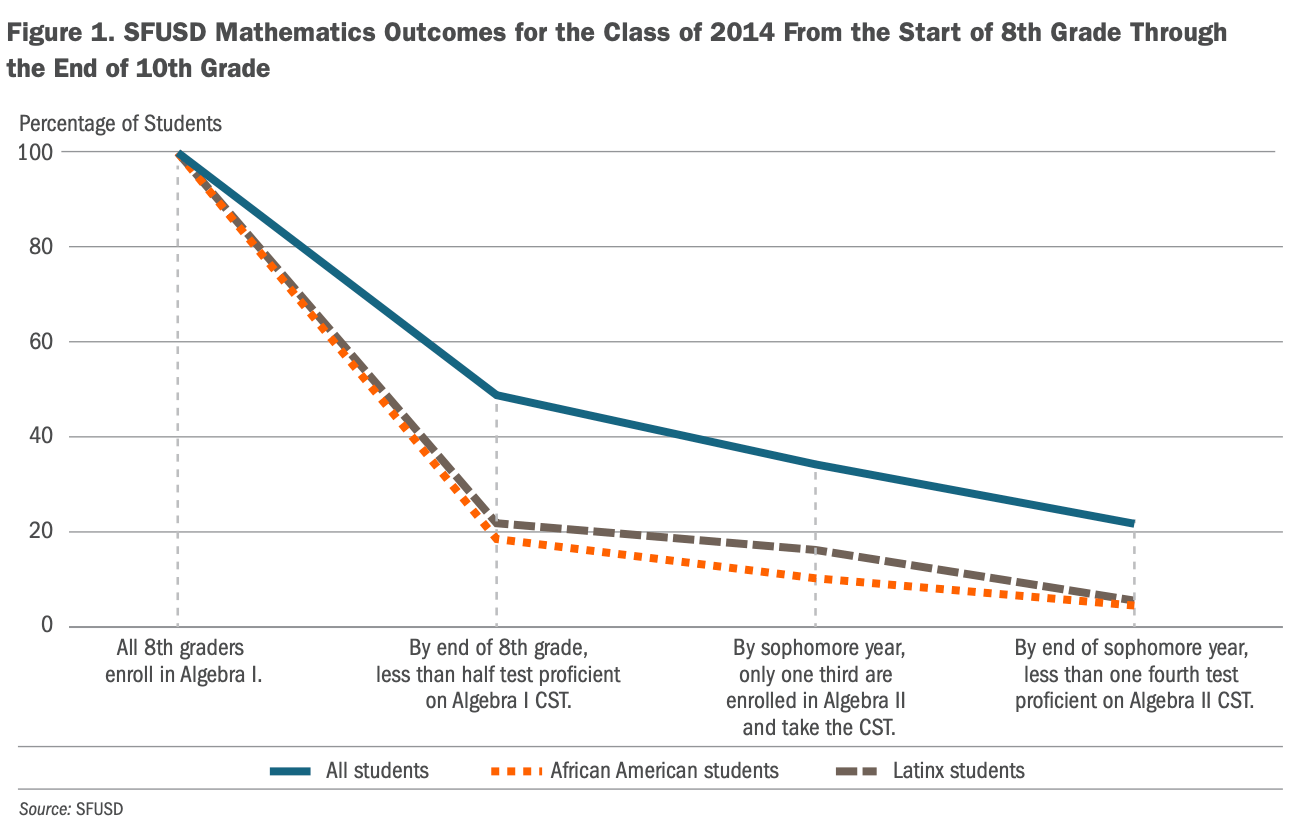

San Francisco Unified School District has played an important role in this discussion. In an important experiment, the district traced student performance from 8th grade through 10 grade and reached a clear conclusion about what happened subsequently: they found that requiring all 8th graders to take Algebra I had not achieved the district's desired result of high proficiency rates in Algebra II in the 10th grade.

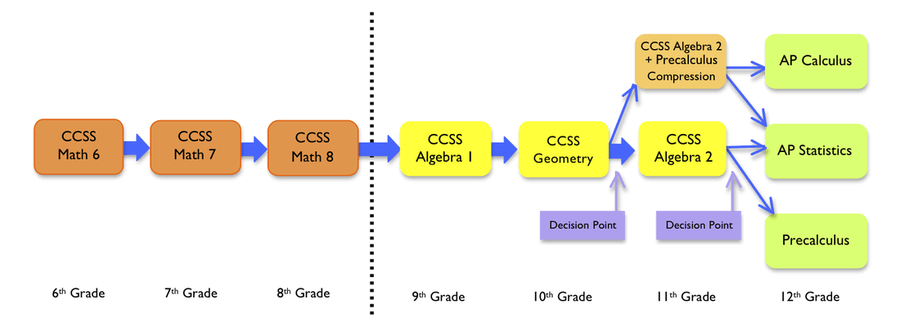

In 2014, the San Francisco Unified School District took a controversial step: it changed the algebra requirement to align with the methodical sequence implied in the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). Over objections that the school district was watering down math and failing to serve the needs of high achieving students, the district eliminated "fast tracks" and moved the Algebra I course to the 9th grade.

What happened after this change was made? Studies show that far fewer students flunked algebra. The rate at which students re-took math courses plummeted. And Black and Latino students enrolled in higher level math courses at a higher rate.

|

More San Francisco Unified School District high school students are taking higher level math classes than ever before. Lizzy Hull Barnes, SFUSD math supervisor, discussed this change with Carol in 2019 on KALW. |

Building on much of this research, California's new draft math framework recommends a number of significant changes in how math is taught.

|

Recommendations in the draft mathematics framework |

|

|---|---|

|

No Tracking |

“End tracking and other exclusionary practices that have historically held students of color behind.” |

|

Consistent expectations |

“Replace ideas of innate mathematics 'talent' and 'giftedness' with the recognition that every student is on a growth pathway. There is no cutoff determining when one child is 'gifted' and another is not.” |

|

Understanding as the goal |

“The ultimate goal ...should not be to get students into and through a course in calculus by twelfth grade but to have established the mathematical foundation that will enable students to pursue whatever course of study interests them when they get to college.” |

The new draft frameworks recommend ending tracking in grades 6 through 8, saying “middle-school students are best served in heterogeneous classes that maintain appropriate challenge and engagement, and build depth of understanding."

Math experts take pains to explain that this does not mean middle school math is being watered down because the grade-eight California Common Core State Standards are actually more rigorous than the previous Algebra I. Want to dig deeper? Here’s a chart that explains the differences.

Teacher preparation

Simply changing the order and scope of math classes does not create improvement. It is the hard and strategic work of teacher preparation that makes the difference.

A significant study of eight school districts in California found that when teachers eliminated tracking and replaced it with challenging mathematics courses for all of their students, students achieved at significantly higher levels both on narrow state tests and on broader, conceptual tests of mathematics. This changing approach to math comes at a particularly precarious time as California has a significant shortage of math teachers. But there may be a silver lining. Both the state and federal government are pouring much-needed money into school districts in a way that can fund more teacher training.

But but but….what about calculus?

The proposed new frameworks coincide with recommendations by both the University of California and Stanford. Both have dropped calculus as a recommended admission requirement. Both warn against speed math. According to a statement from the University of California, “choosing an individually appropriate course of study is far more important than rushing into advanced classes without first solidifying conceptual knowledge.“

What’s Next?

One large issue still causing the grinding of teeth is how to meet the needs of truly gifted students who need acceleration.

According to a statement of the California Association for the Gifted, “the student most neglected, in terms of realizing full potential, is the gifted student of mathematics. Outstanding mathematical ability is a precious societal resource, sorely needed to maintain leadership in a technological world.”

The next draft of the frameworks, scheduled to be posted in late June 2021, will include specific guidance on acceleration (including middle school acceleration) and serving high achievers and gifted students. After the next revised version is posted, you can submit comments to [email protected]

What Do You Think?

Is this new framework a step too far or a smart approach that addresses equity?

Even though local school districts make the final decision on what courses to offer, should the frameworks recommend that all students take the same course work in middle school?

Let us know what you think.

Tags on this post

All Tags

Academia Khan Acoso acreditación Actitud Administradores Agallas Álgebra Ambiente escolar Aprendizaje Aprendizaje Ampliado Aprendizaje basado en proyectos Aprendizaje socioemocional Artes Asistencia Asociación de Maestros de California Asociación de Padres y Maestros Atención plena Ausencias Bonos de obligación Brecha de desempeño Burbank Calidad Calificación de escuelas Calificaciones en pruebas Cambio Canción Carol Dweck Carrera Cerebro Certificación CHAMP Ciencia Cierre de escuelas Civismo Comparaciones nacionales Concurso Consejeros Consejo escolar Control local Costo de educación Creatividad Crecimiento económico Crucigrama CSBA Currículo común cursos de estudios étnicos Datos Después de clases Día de la Independencia Diálogo dislexia Distritos Diversidad Dotado DREAM Act EACH EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Educación bilingue Educación del carácter Educación especial Educación sexual Educación universal Elección Elección de escuela Enlaces guía Equidad Escasez de maestros Escuelas chárter Escuelas comunitarias Escuelas en casa Escuelas Magnet Escuelas privadas Esfuerzo Estándares Estudiantes en riesgo Estudiantes que están aprendiendo inglés estudiantes sin hogar Estudios étnicos Evaluación Evaluación nacional de progreso educativo Éxito Federal Filantropía Financiamiento Financiamiento local Fondos por categorías Ganadores Gastos Gobierno local Gráfica Grupos de presión Guía para padres líderes Historia Horas de oportunidad Huelga Humanidades Impuestos a la propiedad Impuestos prediales Índice de desempeño académico Indignación Indocumentado Infraestructura Iniciativas Instalaciones Internacional Investigación Jerga Kindergarten La Ley Brown LCFF Lectura Ley Cada Estudiante Triunfa Ley Que Ningún Niño Se Quede Atrás Liderazgo Límites de distritos Litigación Lotería Maestros mantequilla de cacahuate Mapa Mapa del sitio Marcador Matemáticas Medios de comunicación Mejoramiento Continua Mito Mitos Motivación estudiantil Negociación colectiva Negocio Niñez temprana Noticias falsas Nutrición Organizaciones de gestión para escuelas chárter Padres Pandemia Participación de los padres Pedagogía Pensiones personalizado PISA Plan de responsabilidad de control local Planificación Plantilla Población Pobreza Política Política federal Políticas Premio Prescolar Presupuestos Prezi Proposición 13 Proposición 98 Propósito de la educación Pruebas Reclutamiento de maestros Reforma Requisitos ag Responsabilidad Resumen del año Retención de maestros Rigor rompecabezas Rúbrica de evaluación Salario de maestros Salud Salud mental Se necesita ayuda Serrano vs Priest Sindicatos Sorteo SPSA STRS Sueño Suicidio Superintendente Suspensiones Tablero Talento Tamaño de clases Tareas escolares Tasas de graduación Tecnología Tecnología en la educación Tiempo dedicado a la tarea Tiempo en la escuela Trump Universidad Vacunación Vales Valores Vapeando Verano Vídeo Voluntariado Voluntarios Voto Voz del estudianteSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .